Clybourne Park and Housing

Get Tickets

Clybourne Park and Housing - Resources to learn more

Bruce Norris's Pulitzer Prize-winning play Clybourne Park was written as a spin-off to Lorraine Hansberry’s 1959 drama “A Raisin in the Sun.” It's set before and after the events of Hansberry’s work in a house in a fictional neighborhood in Chicago. Act I takes place in 1959, when a white couple is preparing to sell their house to the neighborhood’s first Black family. But during a time of racial strife, not everyone approves of the impending sale.

Circumstances are reversed in Act II, set in 2009, when a white couple wants to purchase the same home, now located in a predominately Black neighborhood on the verge of gentrification. The couple’s plan to demolish and rebuild the property leads to tension-filled encounters with members of the neighborhood’s housing board.

The play presents two different opinions on who “owns” a neighborhood, and who should be allowed to dictate who will move in and how the neighborhood will grow and change.

Below, explore some key terms and ideas around housing and gentrification and learn more about how these issues play out right here in Denver and Jefferson County.

Gentrification: a process of neighborhood change that includes economic change in a historically disinvested neighborhood — by means of real estate investment and new higher-income residents moving in – as well as demographic change – not only in terms of income level but also in terms of changes in the education level or racial make-up of residents.

Gentrification is complex — to understand it better, here are three key things to consider:

- Historic conditions, especially policies and practices that made communities susceptible to gentrification

- Disinvestment and investment patterns of the central city

- Impact on communities

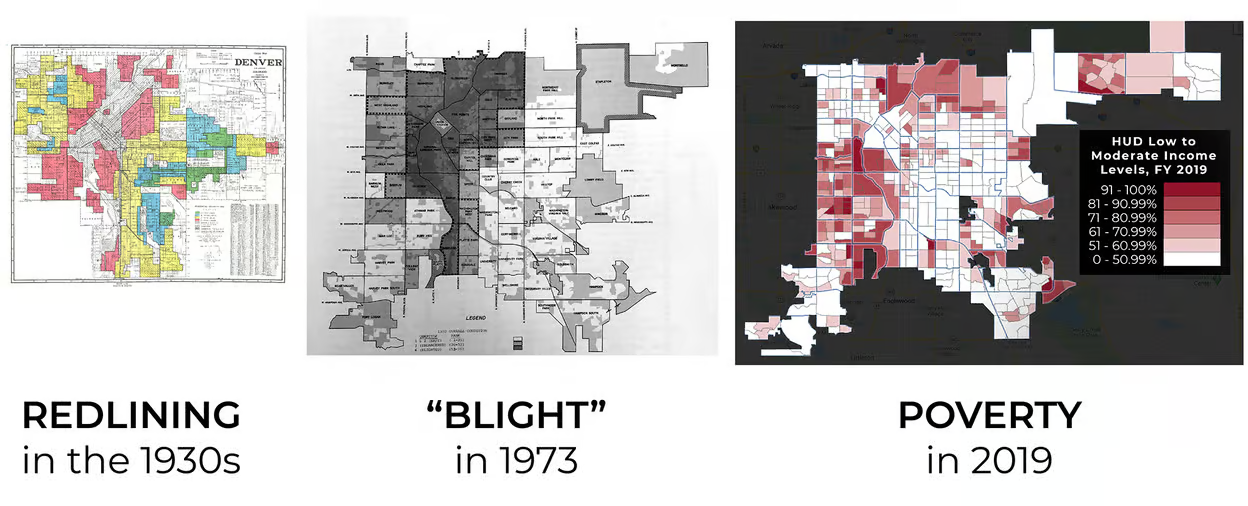

Redlining: From the 1930s through the late 1960s, standards set by the federal government and carried out by banks explicitly labeled neighborhoods home to predominantly people of color as “risky” and “unfit for investment.” This practice meant that people of color were denied access to loans that would enable them to buy or repair homes in their neighborhoods.

Redlining was a process in which the Home Owners’ Loan Corporation (HOLC), a federal agency, issued neighborhood ratings to guide investment. This policy is named for the practice of categorizing neighborhoods as red or “hazardous” on HOLC maps, meaning that these neighborhoods were deemed the riskiest in terms of loan issuance. These neighborhoods were predominantly home to communities of color, and this is no accident; the “hazardous” rating was in large part based on racial demographics. In other words, redlining was an explicitly discriminatory policy. Redlining made it hard for residents to get homeownership or maintenance loans and led to disinvestment cycles.

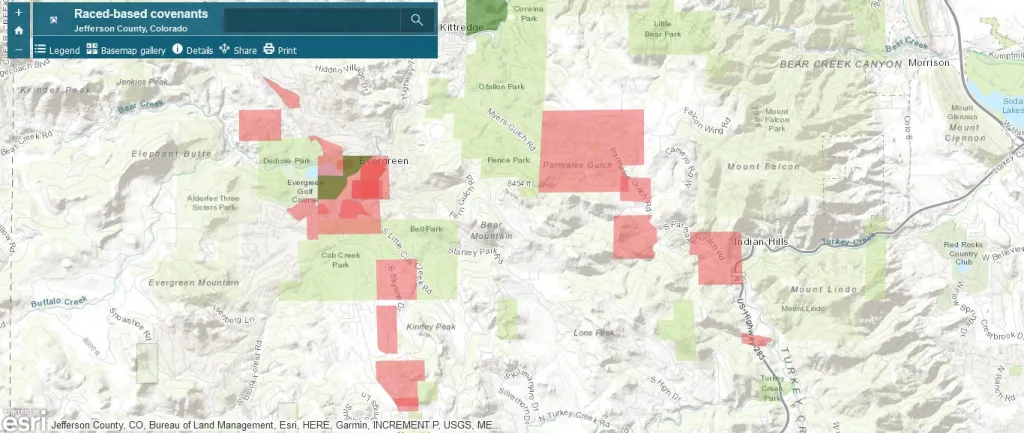

A portion of a map shows housing areas where racially restrictive covenants were located in Jefferson County, specifically Evergreen and the Indian Hills areas. Red areas had the covenants, green areas did not and yellow areas were unclear.

White flight: Other housing and transportation policies of the mid-20th century fueled the growth of mostly white suburbs and the exodus of capital from urban centers, in a phenomenon often referred to as “white flight.” The mortgage component of the GI Bill is an example of a program that fueled white flight—the program guaranteed low-cost mortgage loans for returning WWII soldiers. However, discrimination limited the extent to which black veterans were able to purchase homes in the growing suburbs. In fact, the Federal Housing Administration (FHA) largely required that suburban developers agree not to sell houses to Black people in order for the developers to access these guaranteed loans.

Urban Renewal: Left behind in urban/inner-city neighborhoods, low-income households and communities of color bore the brunt of highway system expansion, electrical grid substations, and deteriorating structures. Neighborhood blight resulted in the mass abandonment of homes, businesses, and neighborhood institutions that set the stage for widespread public and private disinvestment in the decades that followed.

In Denver, these neighborhoods included Globeville, Elyria-Swansea, Five Points, Cole, Whittier, La Alma/Lincoln Park, Auraria, Highland, and others nearest I-25 and I-70 corridors.

Gentrification may look like:

-

Real estate speculation involves investors flipping properties for large profits, high-end development, and landlords looking for higher-paying tenants.

-

Increased investment in neighborhood amenities, like transit and parks.

-

Changes in land use, for example, from industrial land to restaurants and storefronts.

-

The neighborhood's character has changed as community-run businesses have been replaced by businesses catering to new residents’ needs.

Impact of gentrification on communities:

-

While increased investment in an area can be positive, gentrification is often associated with displacement. In some of these communities, long-term residents cannot stay to benefit from new investments in housing, healthy food access, or transit infrastructure.

-

Another impact of displacement to consider is cultural displacement. Even for long-time residents who are able to stay in newly gentrifying areas, changes in the make-up and character of a neighborhood can lead to a reduced sense of belonging or feeling out of place in one’s own home.

Resources to learn more

- How Denver Neighborhoods Got Their Shapes - The Denverite

- Mapping Inequality in Denver - Explore the development of neighborhoods in Denver like Five Points, and how they have changed over time.

- Mapping Historic Race-Based Property Covenants in Jefferson County, Colorado - Official, historic real estate documents from Jefferson County, Colorado reveal patterns of systemic racism.

-

A look at the suburbs: Map experts dig for roots of racial separation in metro Denver neighborhoods.

-

Colorado Gives Foundation: Bringing Affordable Workforce Housing to Jeffco

- Affordable housing map in Jefferson County, Colorado

- Jefferson County Human Services

- Mile High United Way / 211 Colorado

- Foothills Regional Housing